by

Damien F. Mackey

“And just as Judas Maccabeus is promised divine aid in a dream before his victory

over Nicanor, so Constantine dreams that he will conquer his rival Maxentius”.

Paul Stephenson

Some of the Greek (Seleucid) history, conventionally dated to the last several BC centuries, appears to have been projected (appropriated) into a fabricated Roman imperial history of the first several AD centuries.

Most notably, in this regard, is the supposed Second Jewish Revolt against emperor Hadrian’s Rome, which - on closer examination - turns out to have been the Maccabean Jewish revolt against Antiochus ‘Epiphanes’, of whom Hadrian is “a mirror image”. See e.g. my series:

Antiochus 'Epiphanes' and Emperor Hadrian. Part One: "… a mirror image

beginning with:

For more on this, see:

and

and

Judas Maccabeus and the downfall of Gog

Now, last night (2nd December, 2019), as I was reading through a text-like book on Constantine: Roman Emperor, Christian Victor (The Overlook Press, NY, 2010), written by Paul Stephenson, I was struck by the similarities between the Dyarchy (Greek δι- "twice" and αρχια, "rule") - which later became the Tetrarchy (Greek τετραρχία) of the four emperors - on the one hand, and, on the other hand, the Diadochoi following on from Alexander the Great. Concerning the latter, we read (The Jerome Biblical Commentary, 1968, 75:103): “With Alexander’s death, the leadership of several successors (Diadochoi) was ineffectual, and finally a fourfold division of the empire took place”.

Compare the Roman Tetrarchy with the “fourfold division” of Alexander of Macedon’s empire.

Added to this was the parallel factor of the ‘Great Persecution’ against Christians (c. 300 AD, conventional dating), and, of course, the infamous persecution of the Jews by Antiochus ‘Epiphanes’.

And I have already pointed to similarities between one of the four Roman emperors, of the time of Constantine, Galerius, and Antiochus ‘Epiphanes’:

King Herod ‘the Great’, Sulla, and Antiochus IV ‘Epiphanes’. Part Two: Add to the mix Gaius Maximianus Galerius

But these are the sorts of similarities of which Paul Stephenson (author of the book on Constantine) is also aware (on p. 128 below he uses the phrase “the remarkable coincidences”).

P. 109:

Lactantius’ On the Deaths of the Persecutors is the best and fullest account of the period 303-13 and this is indispensable. But it is also an angry screed, with no known model in Greek or Latin literature, nor in Christian apologetic. Not only did Lactantius delight in the misfortune and demise of the persecuting emperors, he also attributed them to the intervention of the god of the Christians, defending the interest of the faithful. Such an approach rejected the very premise on which martyrs had accepted death at the hands of their persecutors: that their god did not meddle in earthly affairs to bring misfortune upon Roman emperors. This was the first step in articulating a new Christian triumphalist rhetoric, which we shall explore more fully in later chapters.

In doing so, Lactantius drew on an Old Testament model, the Second Book of Maccabees, which still forms an accepted part of the Orthodox canon. Thus, the opening refrain of each text thanks God for punishing the wicked, and the agonizing death of Galerius mirrors that of Antiochus Epiphanes (2 Maccabees 9). And just as Judas Maccabeus is promised divine aid in a dream before his victory over Nicanor, so Constantine dreams that he will conquer his rival Maxentius.

P. 127

Lactantius took great pleasure relating [Galerius’] death as divine punishment for his persecutions, describing his repulsive symptoms and the failure of pagan doctors and prayers to heal him.

Here I (Damien Mackey) will take the description from:

“And now when Galerius was in the eighteenth year of his reign, God struck him with an incurable disease. A malignant ulcer formed itself in the secret parts and spread by degree. The physicians attempted to eradicate it… But the sore, after having been skimmed over, broke again; a vein burst, and the blood flowed in such quantity as to endanger his life… The physicians had to undertake their operations anew, and at length they cauterized the wound… He grew emaciated, pallid, and feeble, and the bleeding then stanched. The ulcer began to be insensible to the remedy as applied, and gangrene seized all the neighboring parts. It diffused itself the wider the more the corrupted flesh was cut away, and everything employed as the means of cure served but to aggravate the disease. The masters of the healing art withdrew. Then famous physicians were brought in from all quarters; but no human means had any success… and the distemper augmented. Already approaching to its deadly crisis, it had occupied the lower regions of his body, his bowels came out; and his whole seat putrefied. The luckless physicians, although without hope of overcoming the malady, ceased not to apply fermentations and administer remedies. The humors having been repelled, the distemper attacked his intestines, and worms were generated in his body. The stench was so foul as to pervade not only the palace, but even the whole city; and no wonder, for by that time the passages from waste bladder and bowels, having been devoured by the worms, became indiscriminate, and his body, with intolerable anguish, was dissolved into one mass of corruption.”

P. 128

… Already dying [Galerius] issued the following edict [ending persecution] ….

…. Lactantius cites the edict in full. The story has much in common with the account of the death of Antiochus, persecutor of the Jews in the Second Book of Maccabees. Lactantius must have been struck by the remarkable coincidences, and borrowed Antiochus' worms and stench.

….

The plot now thickens, with the heretical Arius also dying a horrible (Antiochus-Galerius) type of death:

P. 275

Under imperial instruction, Arius was to be marched into church and admitted into full communion, but he never made it. Tradition holds that he died on the way, a hideous death reminiscent of Galerius', which in Lactantius' account drew heavily upon the death of Antiochus, persecutor of the Jews in 2 Maccabees. ….

Part Two:

Constantine more like ‘Epiphanes’

Some substantial aspects of the life of Constantine seem to have been lifted

right out of the era of king Antiochus IV ‘Epiphanes’ and the Maccabees.

As briefly noted in Part One:

Constantine’s victory over Maxentius is somewhat reminiscent of the victory over Nicanor by the superb Jewish general, Judas Maccabeus.

“And just as Judas Maccabeus is promised divine aid in a dream before his victory over Nicanor, so Constantine dreams that he will conquer his rival Maxentius”.

Other comparisons can be drawn as well.

For instance, Constantine’s army, too, was significantly outnumbered by that of his opponent.

Again, after Constantine’s victory the head of Maxentius was publicly paraded:

“His body was recovered, his head removed, then mounted on a lance and paraded triumphantly by Constantine's men”.

Cf. 2 Maccabees 15:30-33):

Could this be the origin (in part) of the Excalibur (King Arthur) legends?

For Constantine apparently occupies a fair proportion of Arthurian legend according to:

Constantine the Great, who in AD 306 was proclaimed Roman emperor in York, forms 8% of Arthur’s story, whilst Magnus Maximus, a usurper from AD 383, completes a further 39%. Both men took troops from Britain to fight against the armies of Rome, Constantine defeating the emperor Maxentius; Maximus killing the emperor Gratian, before advancing to Italy. Both sequences are later duplicated in Arthur’s story.

In Part One I had likened somewhat the fourfold division of the empire of Alexander the Great and the tetrarchy of Constantine’s reign, including the case of the emperor Galerius with whom I had previously identified Antiochus IV ‘Epiphanes’:

King Herod ‘the Great’, Sulla, and Antiochus IV ‘Epiphanes’. Part Two: Add to the mix Gaius Maximianus Galerius

And, as I pointed out in the following article, historians can find it difficult to distinguish between the buildings of (the above-mentioned) Herod and those of Hadrian:

Herod and Hadrian

Of chronological ‘necessity’ they must assume that, as according to this article:

In the later Hadrianic period material from the earlier Herodian constructions was reused, resetting the distinctive "Herodian" blocks in new locations.

…. The first pair of roundels on the south side depicts Antinous, Hadrian, an attendant and a friend of the court (amicus principis) departing for the hunt (left tondo) and sacrificing to Silvanus, the Roman god of the woods and wild (right tondo).

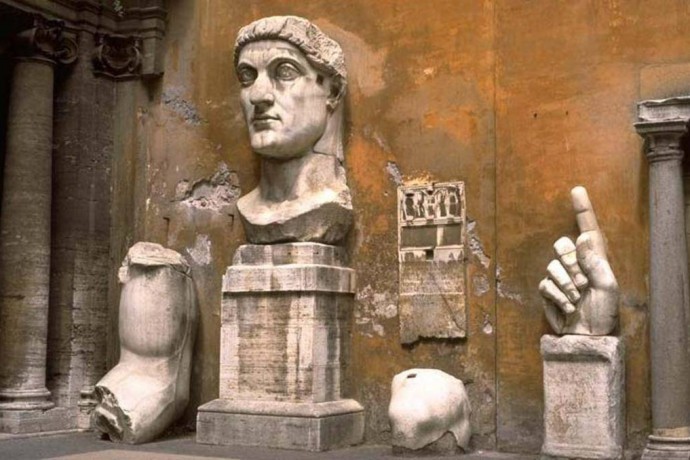

Tondi Adrianei on the Arch of Constantine, Southern side – left lateral, LEFT: Departure for the hunt, RIGHT: Sacrifice to Silvanus

....

The first pair of roundels on the south side depicts a bear hunt (left tondo) and a sacrifice to the goddess of hunting Diana (right tondo).

….

On the north side, the left pair depicts a boar hunt (left tondo) and a sacrifice to Apollo (right tondo). The figure on the top left of the boar hunt relief is clearly identified as Antinous while Hadrian, on horseback and about to strike the boar with a spear, was recarved to resemble the young Constantine. The recarved emperor in the sacrifice scene is likely to be Licinius or Constantius Chlorus.

....

Tondi Adrianei on the Arch of Constantine, Northern side – left lateral, LEFT: Boar hunt, RIGHT: Sacrifice to Apollo

....

On the north side, the right pair depicts a lion hunt (left tondo) and a sacrifice to Hercules (right tondo). The figure of Hadrian in the hunt scene was recut to resemble the young Constantine while in the sacrifice scene the recarved emperor is either Licinius or Constantius Chlorus. The figure on the left of the hunt tondo may show Antinous as he was shortly before his death; with the [first] signs of a beard, meaning he was no longer a young man. These tondi are framed in purple-red porphyry. This framing is only extant on this side of the northern facade. ….

Fred S. Kleiner (A History of Roman Art, p. 326, my emphasis) will go as far as to write that “every block of the arch [of Constantine] were [sic] reused from earlier buildings”:

The Arch of Constantine was the largest erected in Rome since the end of the Severan dynasty nearly a century before, but recent investigations have shown that the columns and every block of the arch were reused from earlier buildings. …. Although the figures on many of the stone blocks were newly carved for this arch, much of the sculptural decoration was taken from monuments of Trajan, Hadrian …. Sculptors refashioned the second-century reliefs to honor Constantine by recutting the heads of the earlier emperors with the features of the new ruler. ….

The highly paganised (Sol Invictus) polytheistic worshipping, family murdering, Constantine makes for - somewhat like Charlemagne - a very strange, exemplary Christian emperor.

The whole account of it is vividly narrated in 2 Maccabees 9:1-29.