by

Damien F. Mackey

Scholars variously find

Homer’s classics to be replete with astronomical detail,

or bursting with biblical

allusions, or serving as accurate navigational guides.

Perhaps they encompass all

of this and more.

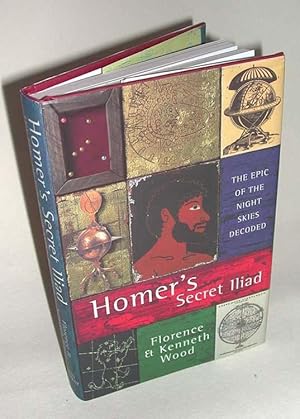

I must

admit to having been completely enthralled by Florence and

Kenneth Wood’s:

Homer's

Secret Iliad

The Epic of the Nights Skies

Decoded.

According

to one review of this book:

Not New Age Kookery

Homer's Secret Iliad is rich in the elaboration of its

hypotheses, such as its discussion of the gods and goddesses as planets, able

to wander throughout the ecliptic band of the skies and, thus, influence the

fate of the mortals, who are the fixed stars, and hence fixed in their actions.

The book provides dozens of examples to bolster each of its arguments, which

are extensive. Florence and Kenneth Wood spent years, following the death of

Edna Leigh in 1991, working through her hypothesis, and fitting [hundreds] ….

of examples into the architecture which Leigh had created.

In the introduction to the book, Kenneth Wood describes the cold

reception received by himself and his wife, when they presented their analysis

to establishment academia. Fortunately, they came in contact with serious

scholars, such as Giorgio de Santillana and Hertha von Deschend, authors of the

1983 Hamlet's Mill, who are themselves investigating how the knowledge

of precession shaped ancient civilizations; their studies have already pushed

the calendar of civilization much farther back than the oligarchy would like.

Work of this sort is very different

from the school of outright New Age kooks, who have many popular books

currently in circulation, which present the evidence of ancient societies'

knowledge of precession and astronomy, as magical, mysterious, or even coming

from aliens from outer space. (One might call this the "Edgar Cayce"

school of history, after the agent who claimed that his knowledge of the

extreme antiquity of Egypt came from his ability to "channel" the

knowledge directly from ancient Egyptians.) Instead, Homer's Secret Iliad

joins the growing list of serious contributions in many disciplines piling up

each year, which demonstrate that mankind has advanced, through his powers of

cognition and discovery, throughout tens of millennium--rather than stumbling

from one cultish civilization to the next over the last 2,500 years. ….

[End of quote]

One

ought to acquire and read this terrific book.

My own

little contribution has been of a biblical nature, regarding mainly The Odyssey:

this

fortuitous apparent connection (Job and Tobit) seeming also to support my view

that the prophet Job was Tobias, son of Tobit. See e.g. my article:

Job's Life and Times

Much

earlier:

St Jerome saw resemblance

of Tobit to Homer's 'The Odyssey'

Felice

Vinci (in Athens

Journal of Mediterranean Studies -

Volume 3, Issue 2 – Pages 163-186) has, for his part, argued

for:

The Nordic Origins

of the Iliad and Odyssey: An Up-to-date Survey of the Theory

The Northern Features of

Homer’s World

Northern Features of

Climate, Clothes, Food, and Vessels

Homer’s world presents northern

features. The climate is normally cold and unsettled, very different from what

we expect in the traditional Mediterranean setting. The Iliad dwells

upon violent storms (i.e., in Il. IV: 275-278, XI: 305-308, XIII: 795-799),

torrential rain and disastrous floods (Il. V: 87-91, XI: 492-495, XIII: 37-141,

XVI: 384-388), and often mentions snow (Il. XII, 156-158), even on lowlands (Il.

XII: 278-286, X: 6-8, XV: 170-171; XIX: 357-358, III: 222). Fog is found

everywhere, e.g., in the "misty sea" (Od. V, 281), and also in Troy

(Il. XVII: 368), Scherie (Od. VII, 41-42), Ithaca (Od. XIII: 189), the

Cyclopes’ land (Od. IX: 144), and so on.

As regards the sun, the Iliad hardly

ever refers to its heat or rays; the Odyssey never mentions the sun

warmth in Ithaca, though it refers to the sailing season. As to the seasons,

there is a parallel between Homer, who mentions only three seasons: winter,

spring and summer, and Tacitus’s Germans, for whom "winter, spring and

summer have meaning and names, but they are unaware of the name and produce of

autumn" (Germania, 26: 4). Vol. 3, No. 2 Vinci: The Nordic

Origins of the Iliad and Odyssey... Clothes described

in the two poems are consistent with a northern climate and the finds of the

Nordic Bronze age. In the episode of the Odyssey in which Telemachus and

Peisistratus are guests at Menelaus’s house in Sparta, the two young men get

ready for lunch after a bath: "They wore thick cloaks and tunics"

(Od. IV: 50–51). The same is said of Odysseus when he is a guest at Alcinous’s

house (Od. VIII: 455-457). Similarly, Nestor’s cloak is "double and large;

a thick fur stuck out" (Il. X: 134) and, when Achilles leaves for Troy,

his mother thoughtfully prepares him a trunk "filled with tunics,

wind-proof thick cloaks and blankets" (Il. XVI: 223-224). Those

"thick cloaks and tunics" can be compared to the clothes of a man

found in a Danish Bronze Age tomb: "The woolen tunic comes down to the

knees and a belt ties it at the waist. He also wears a cloak, which a bronze

buckle pins on his shoulder" (Bibby 1966: 245). Also Odysseus wears

"a golden buckle" (Od. XIX: 226) on his cloak, and "a shining

tunic around his body like the peel on a dry onion" (Od. XIX: 232-233);

all of this fit what Tacitus says of Germanic clothes: "The suit for

everyone is a cape with a buckle (…) The richest are distinguished by a suit

(...) which is close-fitting and tight around each limb" (Germania 17:

1).

Regarding food,

it’s remarkable that fruit, vegetables, olive oil, olives, figs never appear on

the table of Homer’s heroes. Their diet was based on meat (beef, pork, goat,

and game), much like that of the Vikings, who "ate meat in large

quantities, so much so that they seemed to regard the pleasure of eating meat

as one of the joys of life" (Pörtner 1996: 207). Homer’s characters had a

hearty meal in the morning: "In the hut Odysseus and his faithful

swineherd lit the fire and prepared a meal at sunrise" (Od. XVI: 1–2),

like Tacitus’s Germans: "As soon as they wake up (…) they eat; everyone

has his own chair and table" (Germania 22: 1). This individual

table (trapeza) is typical of the Homeric world, too (Od. I: 138).

One should also

note that, while pottery tableware was prevalent in Greece, the Nordic world

was marked by "a stable and highly advanced bronze founding industry"

(Fischer-Fabian 1985: 90), which squares with Homer’s poems, which mention only

vessels made of metal: "A maid came to pour water from a beautiful golden

jug into a silver basin" (Od. I, 136-137); wine was poured "into gold

goblets" (III: 472) and "gold glasses" (I: 142). When a vessel

felt to the ground in Odysseus’ palace, instead of breaking it

"boomed" (bombēse, Od. XVIII: 397). Also lamps (XIX: 34),

cruets (VI: 79), and urns (Il. XXIII: 253) were made of gold. As to the poor,

Eumaeus the herdsman pours wine for his guests "into a wooden cup" (kissybion,

Od. XVI: 52), like the cup Odysseus gives Polyphemus (Od. IX: 346). Wood, of

course, is the cheapest material in the north (Estonia and Latvia have an

ancient tradition of wooden beer tankards). Athens Journal of Mediterranean

Studies April 2017

Nordic

Customs and Archaism of Homer’s World

There are many

remarkable parallels between the Homeric Achaeans and the Nordic world, in the

fields of their social relations, interests, lifestyles, and so on, despite the

time gap.

E.g., Homer’s

habit of giving things and slaves a value in "oxen" – a new vase, decorated

with flowers, was worth "the price of an ox" (Il. XXIII, 885); a big

tripod was worth twelve oxen (Il. XXIII: 703); Ulysses’ nurse Eurycleia had

cost twenty oxen (Od. I: 431), and so on – is comparable to the fact that,

during the first Viking Age, cows were still used "as the current monetary

unit" (Pörtner 1996: 199). A statement from Tacitus bridges these two

distant epochs: "Cattle and oxen (...) are the Germans’ only and highly

valued wealth" (Germania, 5, 1). Besides, the prominence of oxen in

the economy of the Homeric world is another argument in favour of the Nordic

setting, while in the Greek world other kinds of livestock are more important

(one should also consider how important were beef and pork in Achaeans’ diet).

Still on Tacitus,

Karol Modzelewski, by quoting a custom reported in Germania, 11, writes:

"The mention of assembly decisions taken by a peculiar acclamation method,

consisting in brandishing spears, is confirmed by the codifications, dating

back to the 12th century, of the Norwegian juridical traditions, where this

rite is called vapnaták" (Modzelewski 2008: 33). It is remarkable

that the custom of going armed with spear to the assembly is found in Homer:

Telemachus "went to the assembly, he held the bronze spear" (Od. II:

10). Thus a custom dating back to the Homeric world was still present in Viking

Norway of the 12th century.

One should also

note that Odysseus’ ship had a removable mast, a feature typical of all Homeric

vessels: both the Iliad (I: 434, 480) and Odyssey (II: 424, VIII:

52) confirm that setting up and taking down the mast were customary at the

beginning and the end of each mission. This feature was also typical of the

Viking ships, which lowered the mast whenever there was the risk of sudden

gusts or ice formation, which could cause the ship to capsize. Another

structural feature typical of Viking ships, the flat keel, is found also in

Homeric ones, as one can infer from the passage narrating Ulysses’ arrival in

Ithaca, where the Phaeacian ship "mounted the beach by half the

length" (Od. XIII: 114).

Another peculiar

custom of the Homeric heroes is that they got off the chariots and left them

aside during the duels: e.g., the Trojan hero Asius used to fight "on foot

in front of his puffing horses, which the charioteer kept all the time behind

him" (Il. XIII: 385–386). Scholars agree that this way of using the

chariots seems to be absurd and senseless: "No one has ever fought like

the heroes of Homer. They are led to battle in chariot, then they jump off to

fight against the enemy. All that we know about the battle chariots in Eastern

Mediterranean protests against this view of things" (Vidal-Naquet 2013:

573). However, what looks odd in the Mediterranean fits the Nordic world:

according to Diodorus of Sicily, the Celts "employed two-horse chariots,

each with his coachman and warrior, and, when they confronted each other in

war, Vol. 3, No. 2 Vinci: The Nordic Origins of the Iliad and Odyssey... they

used to throw the javelin, then they came down from the chariot and fought with

the sword" (Historical Library 5: 29). Still Diodorus writes that

"Brittany is said to be inhabited by native tribes conforming to their

ancient way of life. In war they use chariots, like the ancient Greek heroes in

the Trojan war" (Historical Library 5: 21). Julius Caesar adds

other details upon the Britains: "When they have worked themselves in

between the troops of horse, leap from their chariots and engage on foot. The

charioteers in the mean time withdraw some little distance from the battle, and

so place themselves with the chariots that, if their masters are overpowered by

the number of the enemy, they may have a ready retreat to their own troops.

Thus they display in battle the speed of horse, together with the firmness of

infantry" (De bello Gallico IV: 33).

So, the chariot

fightings narrated by the Iliad are not absurdities due to the supposed

ignorance of the poet; instead, Homer must be considered the only extraordinary

witness of the Nordic Bronze Age, whose archaic customs survived in Britain

until Caesar’s age.

This confirms what

Stuart Piggott writes: "The nobility of the [Homeric] hexameters should

not deceive us into thinking that the Iliad and the Odyssey are

other than the poems of a largely barbarian Bronze Age or Early Iron Age

Europe. There is no Minoan or Asiatic blood in the veins of the Grecian Muses

(...) They dwell remote from the Cretan-Mycenaean world and in touch with the

European elements of Greek speech and culture (...) Behind Mycenaean Greece

(...) lies Europe" (Piggott 1968: 126). Besides, according to Geoffrey

Kirk, the Homeric poems "were created (...) by a poet, or poets, who were

completely unaware of the techniques of writing," (Kirk 1989: 78) and

"a recent linguistic argument suggests that the Homeric tmesis, i.e. the

habit of separating adverbial and prepositional elements that were later

combined into compound verbs belongs to a stage of language anterior to that

represented in the Linear B tablets. If so, that would take elements of Homer’s

language back more than five hundred years before his time" (Kirk 1989:

88-89).

That’s

why "there is an absolute difference both in extension and quality between

the Mycenaean society and Iliad’s" (Codino 1974: IX): Homer’s

civilization appears more archaic than the Mycenaean one. There is also the odd

case of Dionysus, who is an important god both in the Mycenaean period and in

classical Greece, but is almost unknown in Homer: Homer’s world, therefore,

probably preceded the Mycenaean civilisation, instead of following it.

….